The more I interact with other dentists, the more I realize that many dental professionals are just like everyone else: we avoid going to see a dentist, even when we really need to. I have performed many root canals while suffering from a toothache. I have fitted many sleep appliances and then gone home to snore all night.

It’s like being an architect who lives in a shack: you have access to the best materials, the best tools, and the best knowledge, but you use them purely for other people’s benefit, neglecting your own needs.

It’s like being an architect who lives in a shack: you have access to the best materials, the best tools, and the best knowledge, but you use them purely for other people’s benefit, neglecting your own needs.

As dentists, we understand, probably better than anyone, the importance of good dental care, prophylaxis, and treatments. We preach about the health benefits and facilitate the financing for patients, and then we go home and forget to floss our own teeth. It took a series of experiences to finally get me off my ergonomic saddle chair and into the patient chair.

My Background

I invest a lot of time and money in learning the dental trade. I actually like to read dental textbooks like Dawson, Spear, Ellis, and Misch. I find that studying “old school” discovery and innovation creates a deeper understanding of principles behind the rapidly advancing technology and materials at our disposal. When I read and look at the technicolor photos, I consider the implications and treatment modalities for my patients.

Before I got my bite redone, I would rub my head and jaw at the end of a study session and take some ibuprofen. I even wrote an article in the Fall 2015 issue of Aesthetic Dentistry magazine about taking a Full Arch Reconstruction (FAR) course and treating a friend of mine who suffered from headaches for years. Yet I had suffered from headaches for years, too.

After I returned home from that course, I worked on another full mouth patient and applied what I had learned. I realigned his bite position using neuromuscular-based occlusion, aligning the occlusion based on jaw muscle and TMJ position. He was ecstatic—I had put a stop to decades of headaches for him.

I went on to do the same for dozens more patients, often eliminating their migraines, neck pain, sleep apnea, bruxism, etc. I decided to wear my own orthotic at night for clenching and bruxing, and it helped, but it only helped while I wore it.

My bite was a fairly normal Class 1 occlusion and my facial type is brachiofacial. I had a clenching problem that correlated with anterior entrapment. While moving into centric relation, my lower anteriors would hit the palatal of the upper anteriors and slide the jaw posterior, compressing the discal tissue and triggering muscle spasms.

Because I had ground my teeth down for so many years, I had sheared off my canines, eliminating canine guidance or disclusion. In excursive movements, the second molars would hit on the non-working side, causing further discomfort in the anterior temporalis. This pattern continued for several years.

While attending another course with the Dr. Dick Barnes Group (DDBG) in Utah and listening to the instructor, Dr. Jim Downs, discuss muscle pain in malocclusion patients, I found myself massaging the muscles of my head and jaw, as I often did. That day, like most days, I had a deep, awful headache, neck pain, and jaw soreness.

I noticed that Dr. Downs was looking at me—and I saw him glance at my movements. It was almost as if he were to ask, “Are you even understanding any of this?” But he continued the lecture without saying anything. With that one look from him, I knew it was time to commit to doing something.

I noticed that Dr. Downs was looking at me—and I saw him glance at my movements. It was almost as if he were to ask, “Are you even understanding any of this?” But he continued the lecture without saying anything. With that one look from him, I knew it was time to commit to doing something.

Making the Commitment

I had several reasons for not getting the dental work done: most importantly, I had just bought my practice and money was tight. I knew it would be hard to take time off, too. But in that one moment, I knew it was time. Anyone with chronic pain knows that it’s a terrible way to live. In my case, there was an obvious solution that I had used to help others. I was long overdue for a permanent solution myself.

During a course break, Dr. Downs confronted me and gently asked if I was finally going to take care of the issue. Of course he was right. Because Dr. Downs is my mentor, I asked him if he would take my case. I flew from my home in Arizona to Dr. Downs’s practice, LêDowns Dentistry, in Denver, CO, a total of three times for the treatment.

During my first visit, Dr. Downs used the TENS unit to relax the jaw muscles and reduce muscle memory. Then he used the T-Scan® for occlusal analysis, and he made some minor adjustments for equilibration. I left feeling better than when I came, but after a few months my symptoms came creeping back. My anteriors started hitting again.

The lower anteriors had been adjusted so they weren’t the first teeth to hit. We decided that my lower jaw needed to advance forward a few millimeters, and Dr. Downs eliminated the anterior entrapment, which allowed my jaw to come forward and released the pressure and trigger points.

The lower anteriors had been adjusted so they weren’t the first teeth to hit. We decided that my lower jaw needed to advance forward a few millimeters, and Dr. Downs eliminated the anterior entrapment, which allowed my jaw to come forward and released the pressure and trigger points.

Figuring out which muscles were distressed and why requires investigation and homework by the dental provider and the patient. Temporary removable orthotics were critical in preparing my mouth for a permanent occlusal rehabilitation. In my case, I wore a lower thermoplastic orthotic at night, and also when I would do long procedures. It took away my pain, proving that the proposed treatment was the right thing to do.

Dr. Downs graciously involved me in the diagnosis and asked for my input. He instructed me along the way and guided my understanding so that my treatment turned into a master class. It was invaluable in every way.

Prep Day

On the second visit, Dr. Downs prepped 22 teeth and placed the temporaries. After it was done, I took all kinds of pictures because it looked so great. Once the anesthesia wore off, I was able to assess my bite and I got a chill down my spine—all my teeth hit at the proper time and in the proper envelope of function. The next day I woke up with no pain. My head and neck pain simply vanished.

Like many patients, I couldn’t believe how fast the time went during the treatment. I didn’t have any trouble or spasms at all. Then we gave it a day to rest and waited for the anesthesia to wear off before getting the biofeedback. I returned to Dr. Downs’ office the following day where he made some minor adjustments to my teeth. He tested my bite with the T-Scan®—for timing and force—and then I went home to Arizona. I didn’t return to have the finals seated for two months.

After arriving home and settling into daily life, I couldn’t believe the difference. I’d been in denial that I needed dental work. But if I needed proof, this was it: immediate relief from pain. I knew I should have had the work done sooner.

I took really good care of the temps because I’ve had patients who didn’t, and we weren’t able to cement on seat day due to bleeding gums. Therefore, I was constantly brushing, using the AirFloss or Waterpik®, and following the prescription for temporaries that we give everybody—taking my own advice for once!

In addition, I used a tube of the MI Paste® Plus, which I kept with me and applied every morning and afternoon. It’s a calcium-based product with fluoride. It reduces sensitivity and prevents bacteria. A full mouth rehabilitation is such a big investment and I had to travel for each appointment, so I was meticulous about hygiene.

In my case, Dr. Downs left about 2 mm of freeway space, but within a week I had taken that up and started to get another muscle ache on my left temporalis. I traveled to Utah for a continuing education (CE) class that Dr. Downs was teaching, and he made a few adjustments while I was there. The problem was solved.

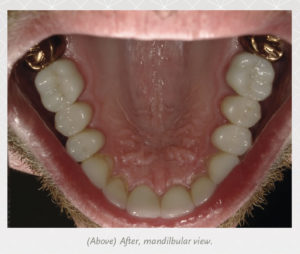

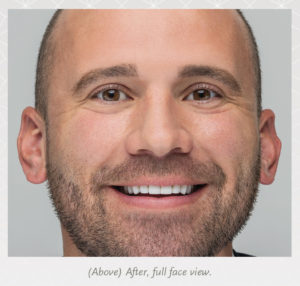

For the entire rehabilitation, Dr. Downs placed 22 crowns, which was a big commitment. I would have had them all done, but Dr. Downs didn’t think it was necessary; we just redesigned my bite a bit. I get compliments on my smile all the time now, and while that’s a great benefit, it didn’t play into my initial decision. I was happy with the look of my original smile.

Results

An important consequence of having a full mouth rehabilitation is that I am now more empathetic with my patients who undergo the same procedure. I can talk about their symptoms from the perspective of a fellow patient. If they have sensitivity, I can say more than, “Oh, that’s normal,” which can feel dismissive. I can say, “Yes, I had sensitivity for two weeks,” and it’s no longer a theoretical or academic statement. Now when patients hear about my personal experience, they think of me as a fellow patient, rather than just the doctor.

I always stress how important it is for patients to care for the temporaries. I give them the MI Paste® Plus, the AirFloss flosser, and an electric toothbrush. I’m more deliberate in my treatment because I know what can cause post-op issues. I also use the laser more than I used to for a better post-op experience and to make the bonding session more predictable.

Now that it’s done, my only regret is that I didn’t do it sooner. I wish I had just saved up and made the commitment earlier, because it would have saved me years of pain. Obviously it’s not just dentists who put off dental treatment; denial is a fairly universal human emotion. But dentists don’t have the excuse of ignorance. If you need treatment, get it. Don’t wait.