Not being a fan of the “fast food” that seems to permeate our culture, I asked a colleague why he always ate at a certain establishment. He stopped for a second, patted his belly, shrugged apathetically and replied, “The food fills the hole and it’s cheap.”

That comment was still in my mind later as I reflected on the decade I spent as a technology consultant in the dental industry. During that time I worked in all kinds of dental practices and witnessed all manner of practice management philosophies. In the past few years I have noticed a rather troubling trend, and I offer my latest experience as a dental patient to illustrate it.

About 18 years ago I broke the two front teeth on my upper arch playing basketball. My parents’ dentist placed two crowns, and I experienced no problems until about five months ago, when I noticed that one of the crowns was loose. I called the dentist I had been visiting the past two years, and I was told by a rather stern-sounding woman that the only appointment available for existing patients was the following Thursday. Not wanting to go through the whole insurance procedure with a new dentist, I relented and made an appointment for that day.

The following Thursday, I made it a point to arrive a few minutes early. As I walked in, the receptionist asked if I had an appointment and told me to sign in. I waited for 35 minutes before I was taken back to the operatory, where the assistant directed me to a chair and left me for another 10 minutes. Upon her return, the assistant asked several questions as she prepped the operatory. I didn’t get the impression that she was really even listening to what I was saying.

Another 10 minutes passed before the dentist came in, pulled my chart, and greeted me in a tone common to healthcare workers who know their patients only by the name on the chart.The dentist asked a few questions similar to those asked previously. He then took the drill and in less than five minutes had removed the loose crown. He told the assistant to take an impression and bring it to him for inspection. With that he stood up and left.

The assistant struggled during the impression process, and she ended up taking three impressions before she had one she thought the dentist would approve. The dentist never came back to check the work—she had to take each impression to him for approval. Once the third impression passed, she made a temporary crown, a poorly fitting one at that, and told me to go to the front desk to schedule my next appointment. At the front desk, I was asked for my co-pay. I received a form showing what my insurance would cover and what I needed to pay before the crown would be placed. I was given a reminder card for my appointment and sent on my way.

I left that appointment feeling like I had been on a dental assembly line. I asked a good friend if his dental visits were similar, and he said, “Anymore, a dentist is like a plumber or a car mechanic. The phone book is full of them, and they all pretty much do the same thing. It’s all just a question of how much they charge and when they can get to you.” This was all so similar to what my portly colleague had said when describing his fast-food experience.

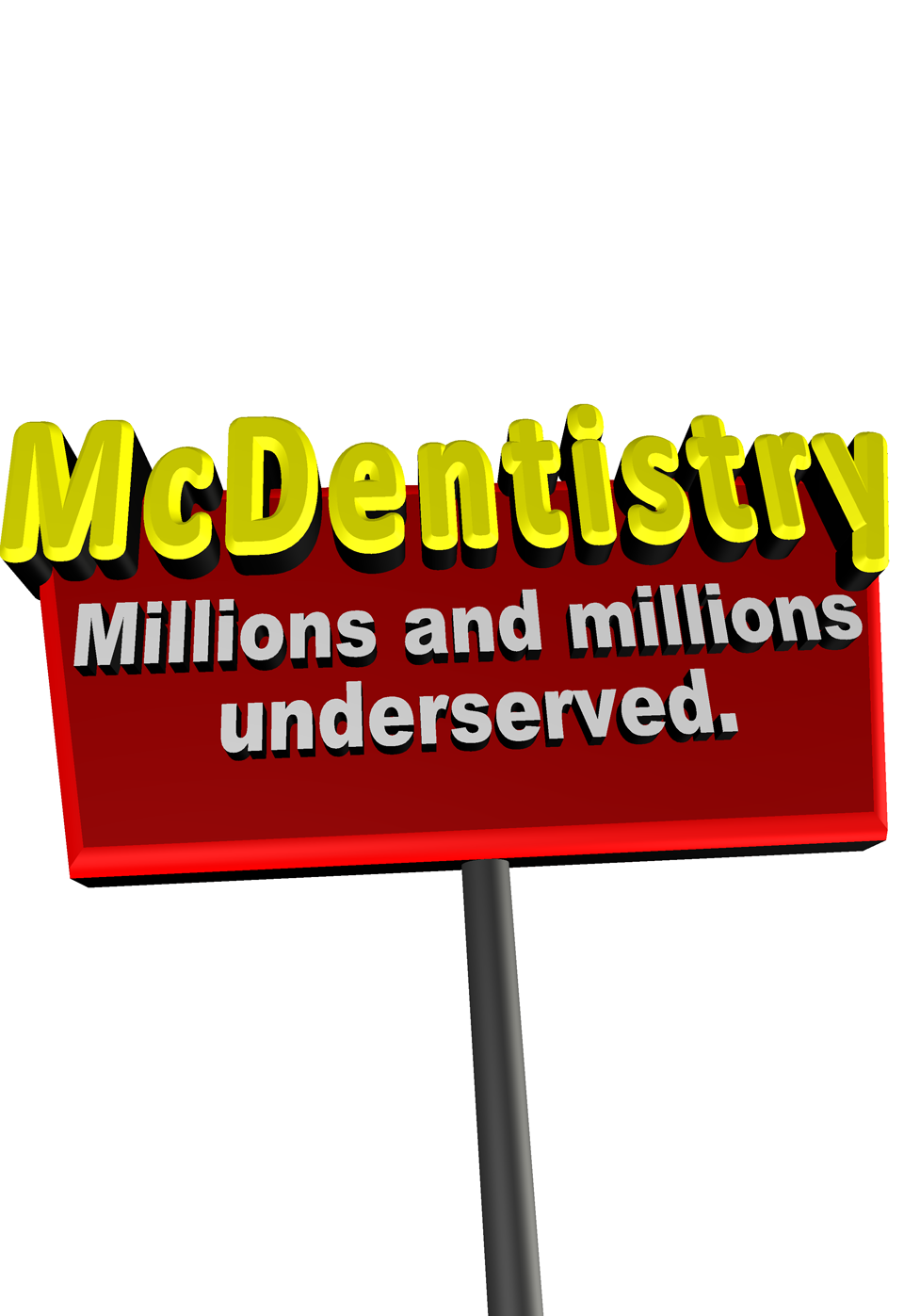

I believe similar experiences are becoming increasingly more common in practices all across the country. The old dental adage of “drill, fill and bill” has evolved into a volume-oriented business model that seeks to treat symptoms without really addressing the root cause. This commodity dental experience—one I call “McDentistry”—involves the conflicting focus of attracting as many new patients as possible and presenting whatever dentistry their insurance will cover. Understanding what is fueling this trend and considering our response will dictate the future of dentistry.

Fear

Fear can be paralyzing and make even good opportunities seem like high-risk gambles. In today’s weakened economy, many dentists have lost sight of what comprehensive dentistry really means. They complain of decreasing numbers of new patients, patients not accepting recommended procedures, and insurance companies continually decreasing what they will cover. Dentists are reluctant to invest in acquiring new skills or technologies. Failing to properly manage these fears and move past them is increasing the appearance that dentistry is a commodity service.

The “new patient fallacy” as I call it is a fear-based belief that to maintain production goals dental practices must constantly attract new patients. While this is commendable, it is often overemphasized and results in a diminished focus on existing patients.

On several occasions the American Dental Association has advised dentists that the best way to diminish the economy’s negative effects is simply to advertise more. Get more patients and all will be well, it says.

Think about it for a moment. To attract more patients, a dentist must increase advertising and offer something that his competitor does not. Often this is a free procedure, or worse, discounted pricing. Consider the profound ramifications discovered by the research department at Eastman Kodak Company:

A 10% cut mandates a 67% increase in production.

A 15% cut mandates a 150% increase in production.

A 20% cut mandates a 400% increase in production.

Both of these strategies will require the dentist to schedule more patients per day to keep production goals. The more patients you pack into a schedule, the less time to find out what those patients truly need beyond treating the symptoms that prompted their visit that day. If you fall into the trap of fixing symptoms, you become a practitioner of expense-based dentistry. Soon your customers will see your relationship as, “How much is this going to cost me?”

Dentists are often fearful of prescribing any treatment that has a high price tag. They must ask themselves, “What is the benefit of getting new patients if you are not confident enough to present the dentistry that is really needed?” Instead of generating more new patients upon whom you can do basic procedures, make it a point to present the comprehensive treatment that all of your patients, especially the existing ones, need.

A primary obstacle to comprehensive dental care is fear that the patient will reject the treatment plan. Often, dentists tailor dental treatment to what they perceive the patient is willing or able to pay. Dentists have told me that instead of presenting an implant to a patient they thought was price conscious, they chose to present a less costly option in which a bridge was used. Now I ask you, over time which of those options is going to be best for the patient?

Look inside and ask, “What kind of dentistry do I want to practice? Expense-based dentistry that patients can get anywhere, or comprehensive dentistry that is presented in terms of value?” People find ways to pay for value, while they “price shop” when they have to pay an expense.

Another factor that I see contributing to the spread of “McDentistry” is dentists’ reluctance to invest in new dental skills and technologies. When the economy is good, dentists don’t think they need to change anything. When the economy is bad, they throw up their hands and say that they can’t afford to invest in their practices. As a result, the practices become stagnant and patients see little to differentiate their dentist from every other dentist in the phone book.

A down economy is the perfect time to invest in your practice. With the decreased patient load you should have ample time to become proficient in implants, advanced occlusion or even full arch reconstruction. Use the down time to hone the communication between you and your staff, so that every patient feels like he or she is getting something that is not available at every office. When you are comfortable with the new and emerging techniques, you will become effective in communicating the benefits of comprehensive dentistry. You will find a satisfaction and prosperity in dentistry that you did not know existed.

Seeing

Too often, under the pressures of production and scheduling, dentists develop blind spots. If they aren’t careful, they will overlook opportunities and instead face a significant loss of potential production, personal fulfillment, and patient satisfaction.

As I reflect on my experience, I am amazed that with all the questions the hygienist and dentist asked, no one seemed to just open their eyes and see what was in front of them. First, only one of the crowns on my two front teeth was loose. Why didn’t the dentist present me with the option of having both crowns redone so they would match more precisely?

Second, I have mild bruxism, yet no one asked me about a night guard or even mentioned treatment options. Had these two simple observations been presented, they would likely have resulted in additional revenue for the dentist. Because he didn’t mention it, I was forced to conclude that he didn’t care or find it particularly important. Being able to see the signs, interpret them, and paint the picture of a comprehensive plan for the patient is a skill that too few dentists seek to develop.

To help dentists avoid this blind spot, I encourage them to do two things daily. First, take time to speak briefly with the patient and look at the whole story the mouth has to tell. During down time, go through patients’ records and find existing patients with needs you can potentially address. Patients see great value in a healthcare provider they perceive as watching out for them.

Second, instruct and include your staff in this process. The time that your assistant spends prepping the patient is a prime opportunity to ask probing questions that can uncover hidden opportunities.

I am reminded of a hygienist who during a routine dental cleaning noticed mild yet unusual wear on the occlusal side of the patient’s teeth. As she worked, the hygienist simply asked if the patient suffered from headaches. The patient shared that she often experienced headaches upon waking.

When the dentist came in, the hygienist shared the information and the dentist, who had invested in training and a TekScan device, suggested treatment that would reduce the wear on the patient’s teeth and get rid of her headaches. Although the treatment was by no means inexpensive, I am certain that when the patient completed it she did not leave wondering if she could have had it done less expensively elsewhere. She was grateful the dentist had helped solve her problem and increase her quality of life.

While some dentists downplay dentistry’s commoditization and say it won’t happen, one need only look at the optometry industry and how megastores control much of the corrective eye-care market. Commodization of dentistry is happening, and the old joke about Walmart putting dental clinics in their superstores isn’t nearly as funny as it used to be.

The McDentistry trend is not one you can fix by simply investing in a nice-looking office. Not even McDonald’s, which has ironically remodeled its restaurants to look more modern and inviting, believes that the practice will elevate their product to a high dining experience. The fast-food industry’s success is built on offering basic products matched to what customers will pay. Is that what the dental industry wants to encourage?

The choice that dentists must make is this: practice comprehensive, value-based dentistry or become one of the many “McDentists” forced to compete on price instead of outcome. The choice is one that will define successful dental practices for years to come.